1969

The Demands of May

On Sunday, May 25, 1969, Black students took action. Their protests challenged the institution to improve the experience of being a Black student at Emory. Emory had begun admitting the first Black students six years earlier, but that moment of progress was eclipsed by Emory’s subsequent inaction in creating an inclusive environment for Black students.

By March 1969, Black students were making direct appeals to the administration to consider their concerns and make positive change. A set of proposals were sent by the Black Student Alliance to the President Sanford S. Atwood at the beginning of March.

By May, the academic year was ending and there had been no substantive communication from university administrators regarding any of the proposals. On May 25, institutional inaction was met by Black students’ direct action; the proposals of March became the demands of May.

What follows is the archival evidence of this history, maintained in the University Archives. By preserving the institutional records of Emory, we can see evidence of Black student activism. Conversations, preserved on paper, both candid and bureaucratic, reveal the actions taken (or not taken), giving us a glimpse into how Black students were active participants in Emory’s history.

1969Explore

Initial Proposals

“Fixing” Emory

Hank Ambrose, President of the Black Student Alliance, sent a list of eight proposals to President Atwood. The proposals were comprehensive, designed to reorient an institutional system that deprioritized Black students’ success and well-being. Administrators no doubt met to address these proposals. Bo Jones, a senior member of the administration, sent his personal thoughts regarding the proposals.

The President’s responses to each proposal ranged from reiteration of old talking points to carefully worded rejections. In many cases, the President’s response called upon the Black students to do the work of fixing Emory by themselves.

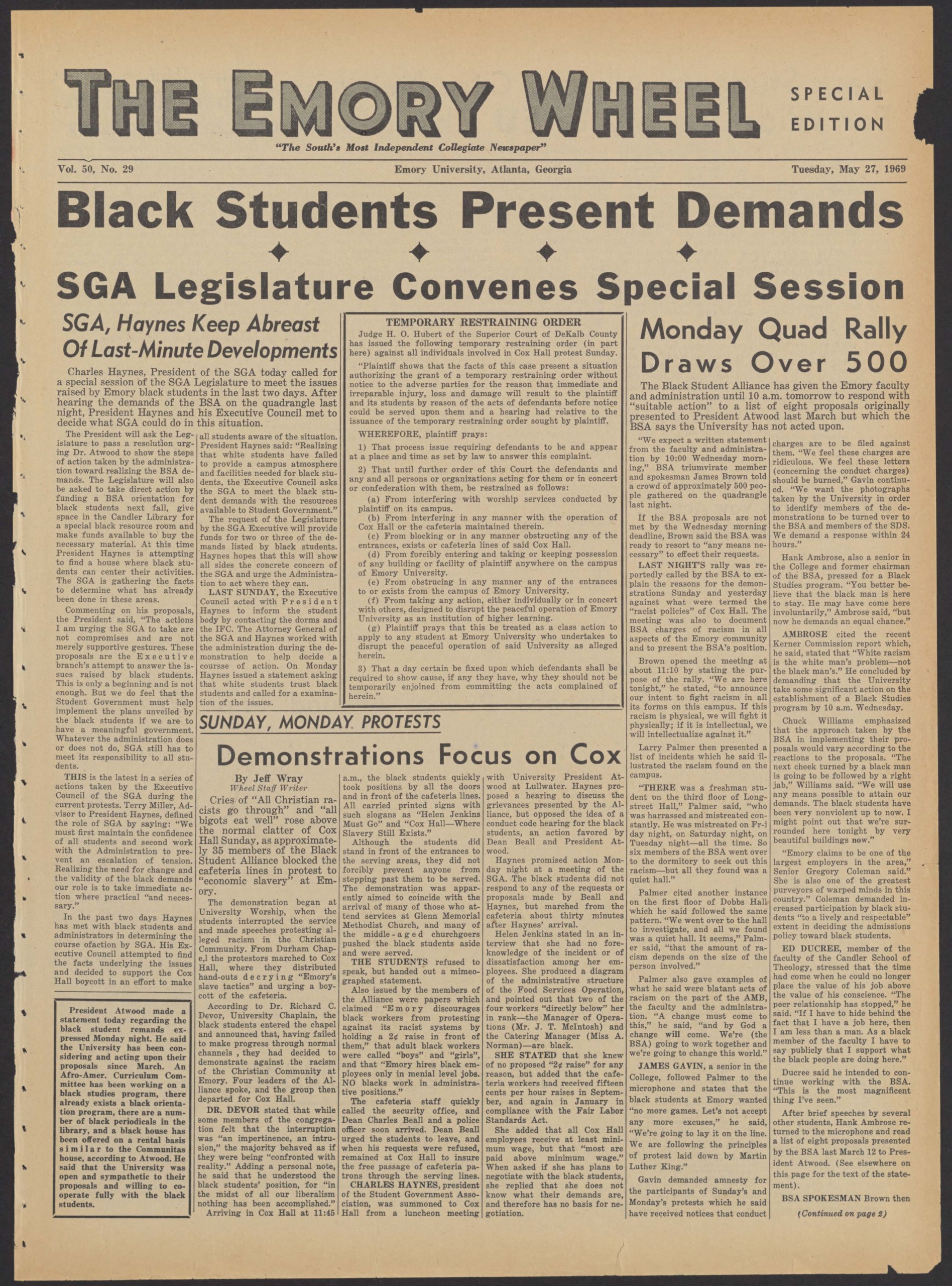

May Protests

“Cox Hall – Where Slavery Still Exists.”

As the semester came to a close, Black students made their voices heard. They marched into Durham Chapel, disrupting Sunday services. They called out what they saw as the moral hypocrisy of those who turned a blind eye to racism at Emory. From the chapel, they made their way to Cox Hall, a hub of activity on campus. They blocked the entrance with signs calling out the unequal treatment of Black employees in the dining halls: “Cox Hall – Where Slavery Still Exists” read one such sign.

The BSA organized a rally the next night to expand on their Sunday protests. On Tuesday, ahead of the convocation that promised to begin a process of forward progress, the institution sought a temporary restraining order against its own students. The convocation was held to a standing room only crowd on Wednesday. The president announced that the restraining order was “rushed” and would be rescinded.

Proposal Progress

Seeking Accountability

The last day of classes came shortly after the protests in late May. Black students had secured a statement of commitment from President Atwood; that Emory would work to eliminate racism on campus. However, correspondence shows how tensions over the summer hadn’t completely gone away, as students sought accountability.

Responses to Protests & Proposals

Negative Responses to Black Student Activism

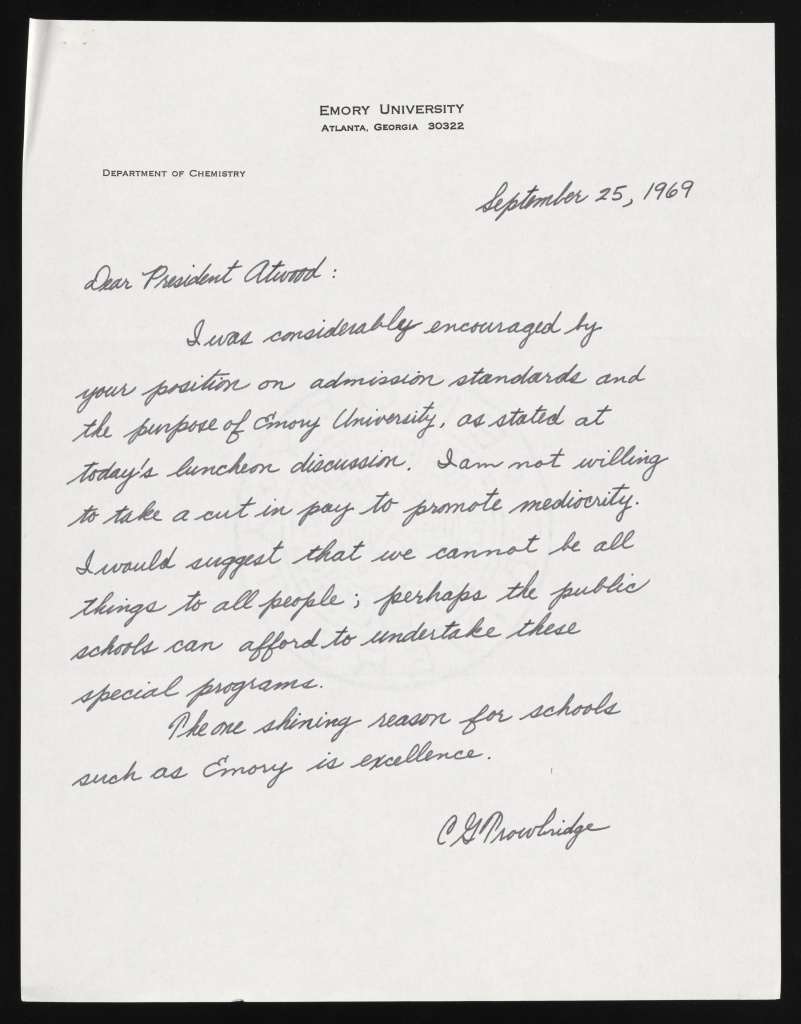

Records in the University Archives also show negative responses to Black student activism. These documents provide evidence for the kinds of attitudes that made progress for Black students difficult. We see evidence of faculty taking both positive and negative views of Black student action. In one response to a faculty screed, President Atwood reveals personally held views that contradict his public statements. The Alumni Council tried to have it both ways: supporting increased attention to issues pointed out by Black students while criticizing the tactics that started the conversation in the first place.

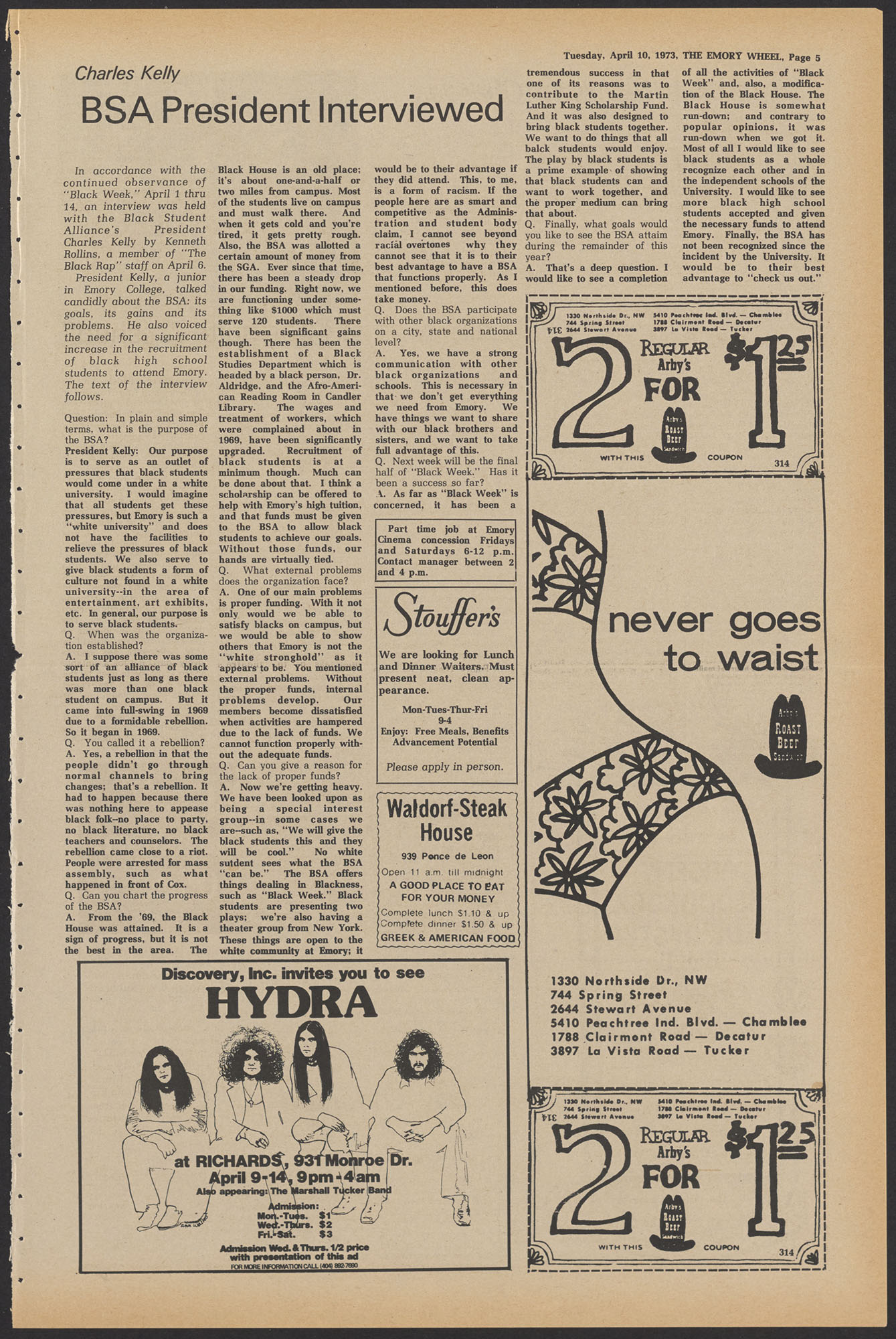

Black Student House

The Black Student Association

Black students demanded a space that could facilitate a greater sense of community and a focal point from which to organize and educate. As BSA member Michael T. Holmes put it in a letter to the Dean of Student Housing: “Living in an isolated white environment can and does destroy the cultural and psychological bonds of a race of people – the Black students at Emory should not be forced to assimilate and thus disintegrate as a Black race.” While Emory did secure a house for use by the BSA, we can see from Wheel articles two years later that the house was not well-placed or well-resourced.

Admissions & Scholarships

Proposed Changes

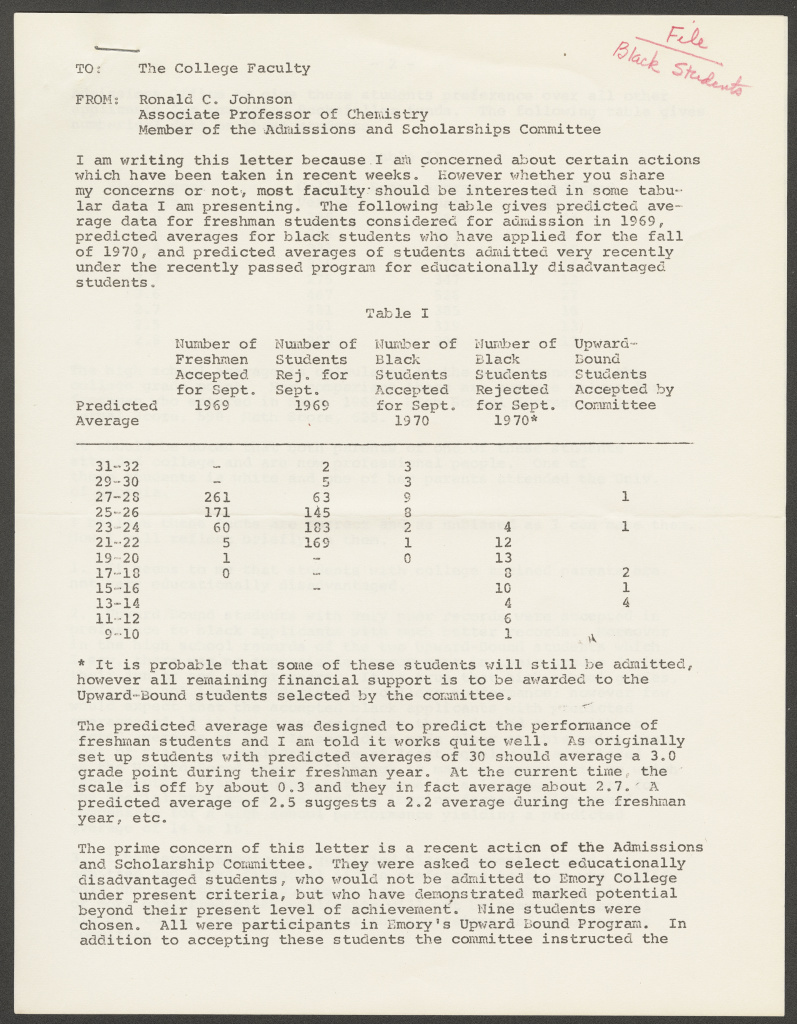

A major area of concern among the BSA was Emory’s commitment to recruiting and retaining Black students. From their perspective, Emory’s admissions policies were part of the problem that excluded Black students from an Emory education. Scholarship money was identified as a major problem as well. Perhaps more controversial than any other issue, proposed changes to admissions and scholarship programs garnered almost a year of debate in various committees.

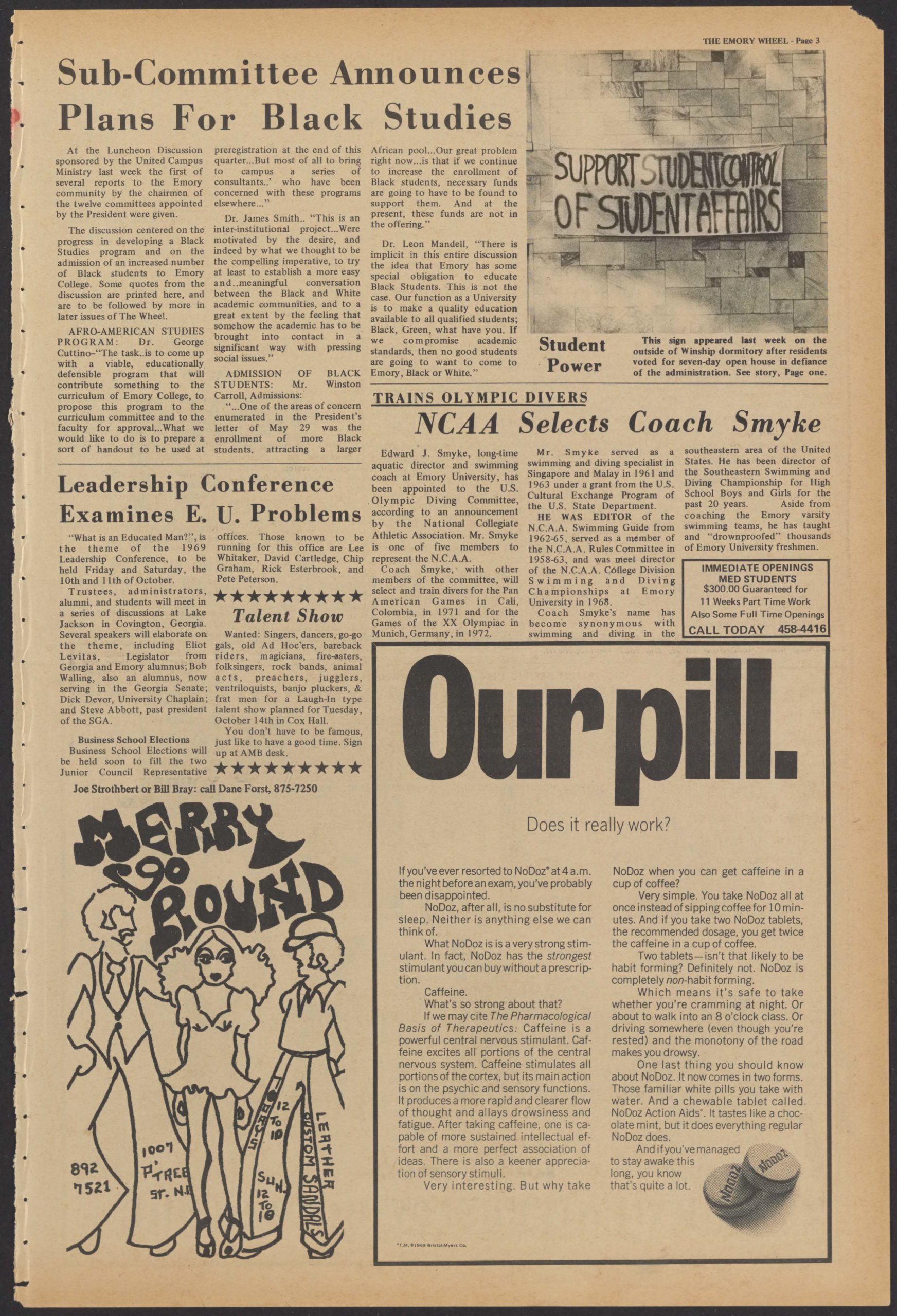

Black Studies

Lack of Progress

Integral to the BSA proposals of 1969 was that Black studies be taught at Emory. Prior the May protests, progress had been made in this area as a subcommittee had been formed to investigate this initiative and presented its recommendation. But by the summer, BSA representative Rena Price requested a pause in discussions, citing general disillusionment with the lack of progress.

Library

By and For Black people

One proposal was that the library should have more academic resources written by and for Black people. The BSA requested periodical subscriptions, books on Black Studies, a Black librarian, and a dedicated space for access to resources. While Emory’s administrators seemed to agree that such changes would be possible, we can see through the subsequent documentation that this proposal was met with bureaucratic slow-walking.

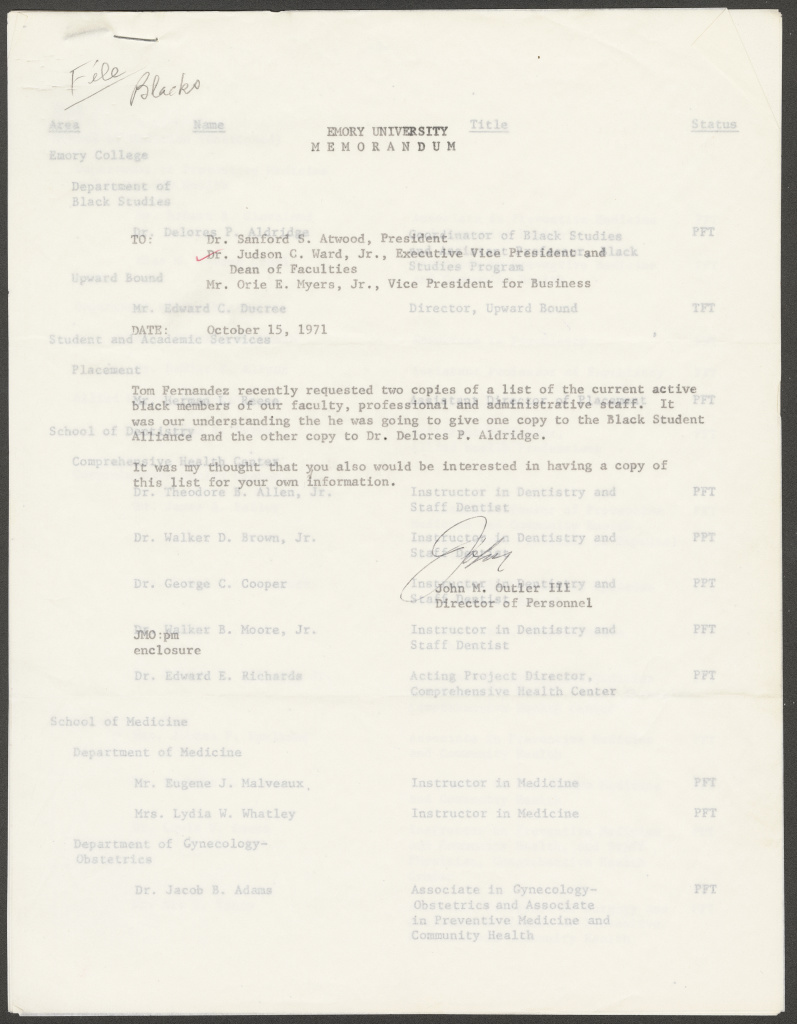

Black Employees & Administrators

Marvin S. Arrington, Sr.

A conspicuous lack of Black staff and administrators meant that Black students felt even more isolated than their white counterparts. The BSA proposed a Black administrator who might provide a crucial bridge to the university and advocate on their behalf. Marvin S. Arrington, Sr., Emory’s first Black graduate from the Law School, was hired in October of 1969.

Student Government

institutional racism

While the BSA took direct action to affect change, Emory’s Student Government Association pursued parallel efforts to eliminate institutional racism at Emory. One of their initial programs was a series of seminars on white racism. SGA also sought to pressure Emory’s leaders to increase enrollment of Black students and create scholarships for Black applicants.