Facing Injustices and Searching for Truths

Oxford College Archives & Special Collections, as an institutional archives, collects materials with an emphasis on documenting the town and college founded on this site under the authority of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1836. The establishment of this institution was the result of Indigenous exploitation, and construction of the original campus was carried out by enslaved laborers. However, there are no primary sources held in the Oxford College archives directly related to the history of the land now occupied and maintained by Oxford College.

Landmarks across the Oxford College campus call attention to its history of slavery and association with the Confederacy. Two academic buildings on the campus quad were constructed prior to the emancipation of enslaved people in Oxford. The nearby Civil War-era cemetery contains a monument honoring soldiers who were buried there during the brief period the campus served as a hospital for wounded Union and Confederate troops, but its inscription and origins in the community denote it as a memorial to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy.

As you explore the items below, think about the following questions:

- Why isn’t there much information on the dispossession of lands and the use of enslaved labor at Emory?

- What stories and voices have been left out of the historical narrative?

Explore

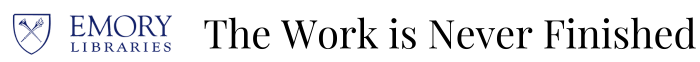

Royce, C. C. & Thomas, C. (1899) Indian land cessions in the United States. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/13023487/.

Emory Approves Land Acknowledgement

Emory’s Oxford and Atlanta campuses were built on land the Muscogee (Creek) people were forced to relinquish. The Emory Board of Trustees approved an official Land Acknowledgment for Emory University in 2021.

According to Emory University President Gregory L. Fenves:

This statement is a recognition of the Muscogee (Creek) and other Indigenous nations, who were displaced in the years before Emory’s founding. It sheds light on a tragic chapter in the Emory story and in the history of the United States. And it also reminds us of the important work that lies ahead—to create a university community that is more inclusive of Native and Indigenous perspectives, learning, and scholarship.

Full statement on Land Acknowledgement

by Emory University President Gregory L. Fenves

Emory Land Acknowledgment

Emory University acknowledges the Muscogee (Creek) people who lived, worked, produced knowledge on, and nurtured the land where Emory’s Oxford and Atlanta campuses are now located. In 1821, fifteen years before Emory’s founding, the Muscogee were forced to relinquish this land. We recognize the sustained oppression, land dispossession, and involuntary removals of the Muscogee and Cherokee peoples from Georgia and the Southeast. Emory seeks to honor the Muscogee Nation and other Indigenous caretakers of this land by humbly seeking knowledge of their histories and committing to respectful stewardship of the land.

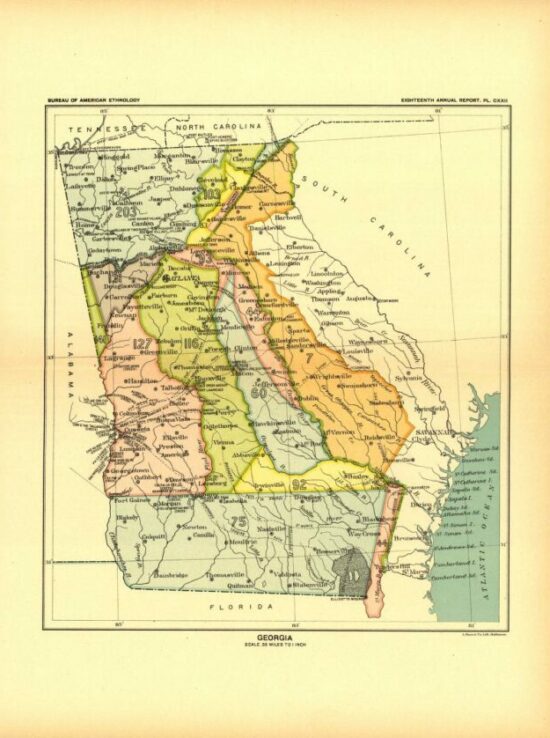

Construction of Oxford Campus

Phi Gamma Hall, Emory University’s oldest surviving academic building, was constructed by enslaved laborers. An early image of Phi Gamma Hall appears in several early Emory publications. A later aerial photo shows the building positioned directly across from Few Hall, constructed during the same era.

Phi Gamma Hall, 1890s

Early image of Phi Gamma Hall.

Zodiac. [1893]. Emory University Yearbooks. [Oxford, Ga.]: Students of Emory College, 1893. Oxford College Archives. https://digital.library.emory.edu/purl/071ngf1vxt-cor.

Aerial photo, early 1900s

Aerial photo of Emory College campus and surrounding area of Oxford, Georgia.

Aerial photo of Oxford, Georgia. Campus views, circa 1945-1990, undated, 4, Box: 10, Folder: 1. Oxford College Photograph collection, Series No. 025. Oxford College Archives. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/6/archival_objects/477703

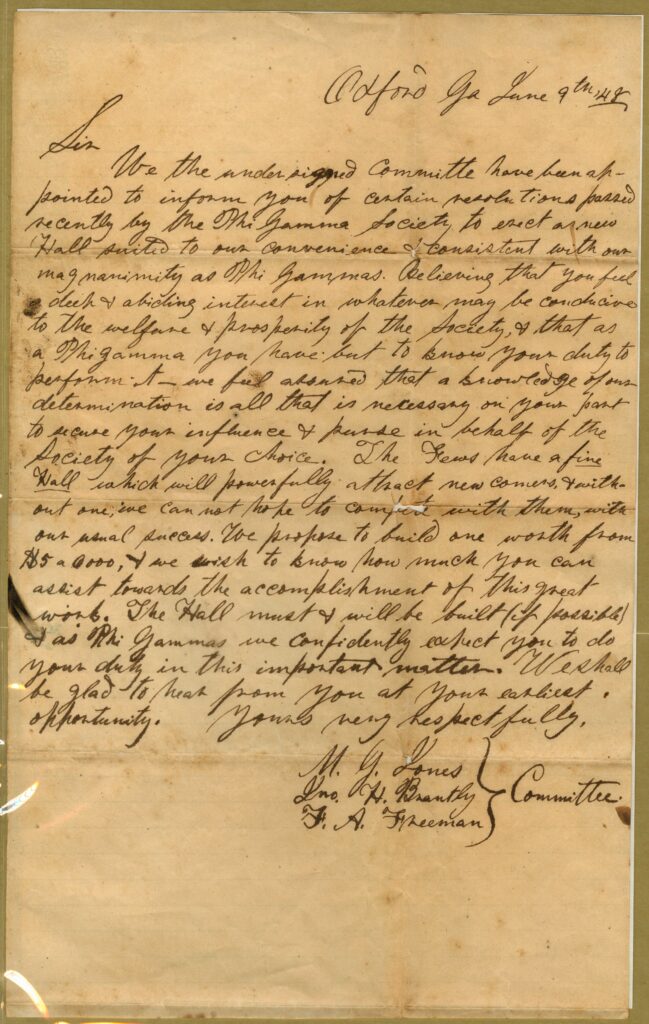

Both the Phi Gamma and Few Literary Societies raised funds from early Emory College alumni for their separate debate halls. The buildings face each other from opposite sides of the north edge of the Oxford College quad. The letter shown here describes the intention to construct both halls, but makes no mention of how that construction will be carried out.

We the undersigned Committee have been appointed to inform you of certain resolutions passed recently by the Phi Gamma Society to erect a new Hall suited to our convenience and consistent with our magnanimity as Phi Gammas….The Fews have a fine Hall which will powerfully attract new comers, and without one we cannot hope to compete with them, with our usual success. We propose to build one worth from $5-6000 and we wish to know how much you can assist towards the accomplishment of this great work.

Phi Gamma letter, 1848

Letter from Emory College alumni soliciting contributions from a fellow member of the Phi Gamma Literary Society.

Phi Gamma Society letter, 1848, Box: 1, Folder: 13. Emory College records, Series No. 016. Oxford College Archives. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/6/archival_objects/476450

Catherine Boyd

Catherine Boyd’s life has been tied to the identity of Emory University and Oxford College through Bishop James Osgood Andrew’s role in the founding of Emory University. Catherine was one of many people enslaved by Bishop Andrew, who was president of Emory College’s Board of Trustees when it opened in 1839. In the 1840s, the issue of slavery divided the Methodist Episcopal church, and Bishop Andrew’s enslavement of Catherine Boyd became a major controversy.

Words have been attributed to Catherine Boyd on several occasions, but there is no known primary source material to corroborate such statements. Personal details are completely absent from the primary sources that reflect her life in Oxford. Without any account to interpret her life in her own voice, what can be known about the woman many have called “Kitty”?

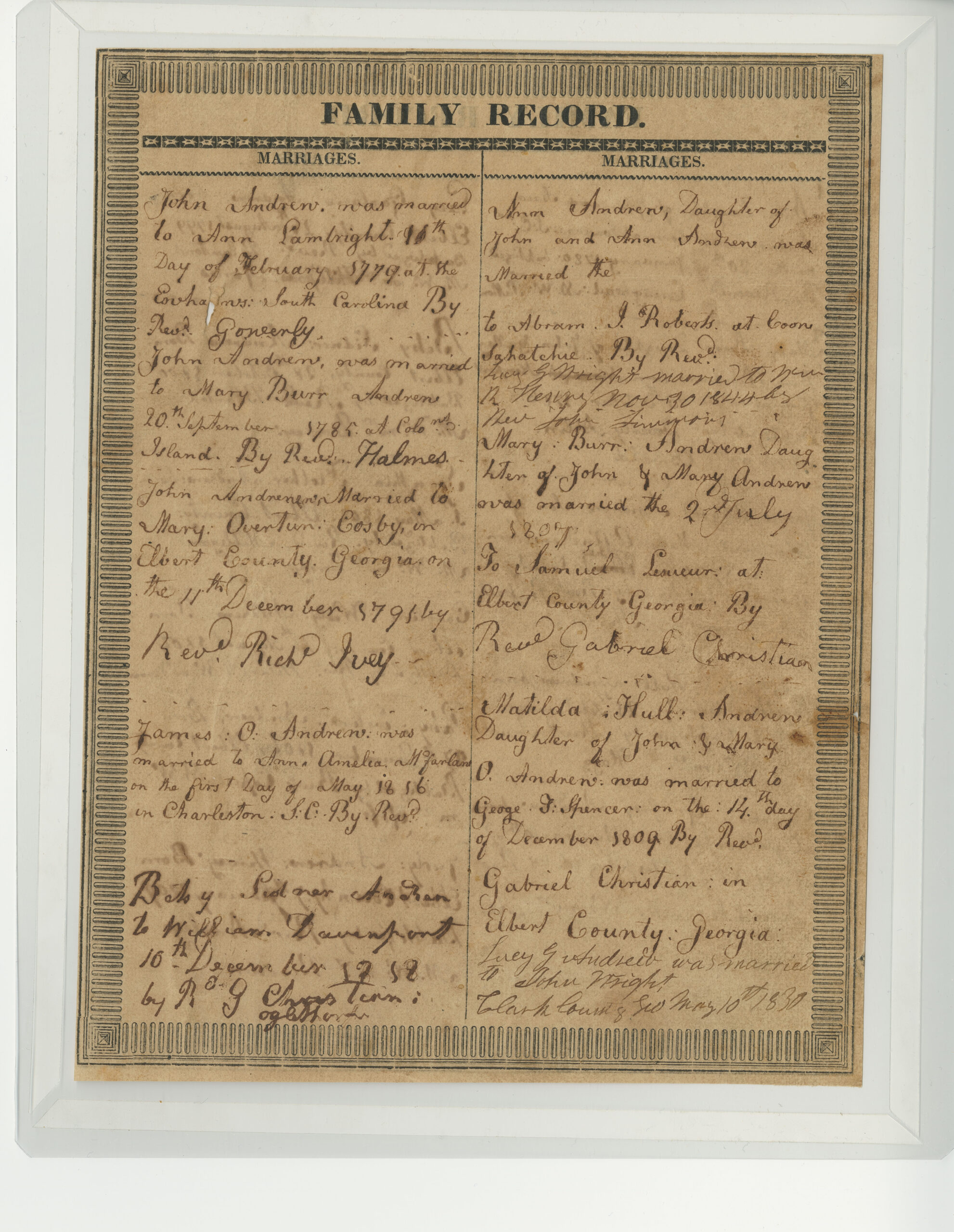

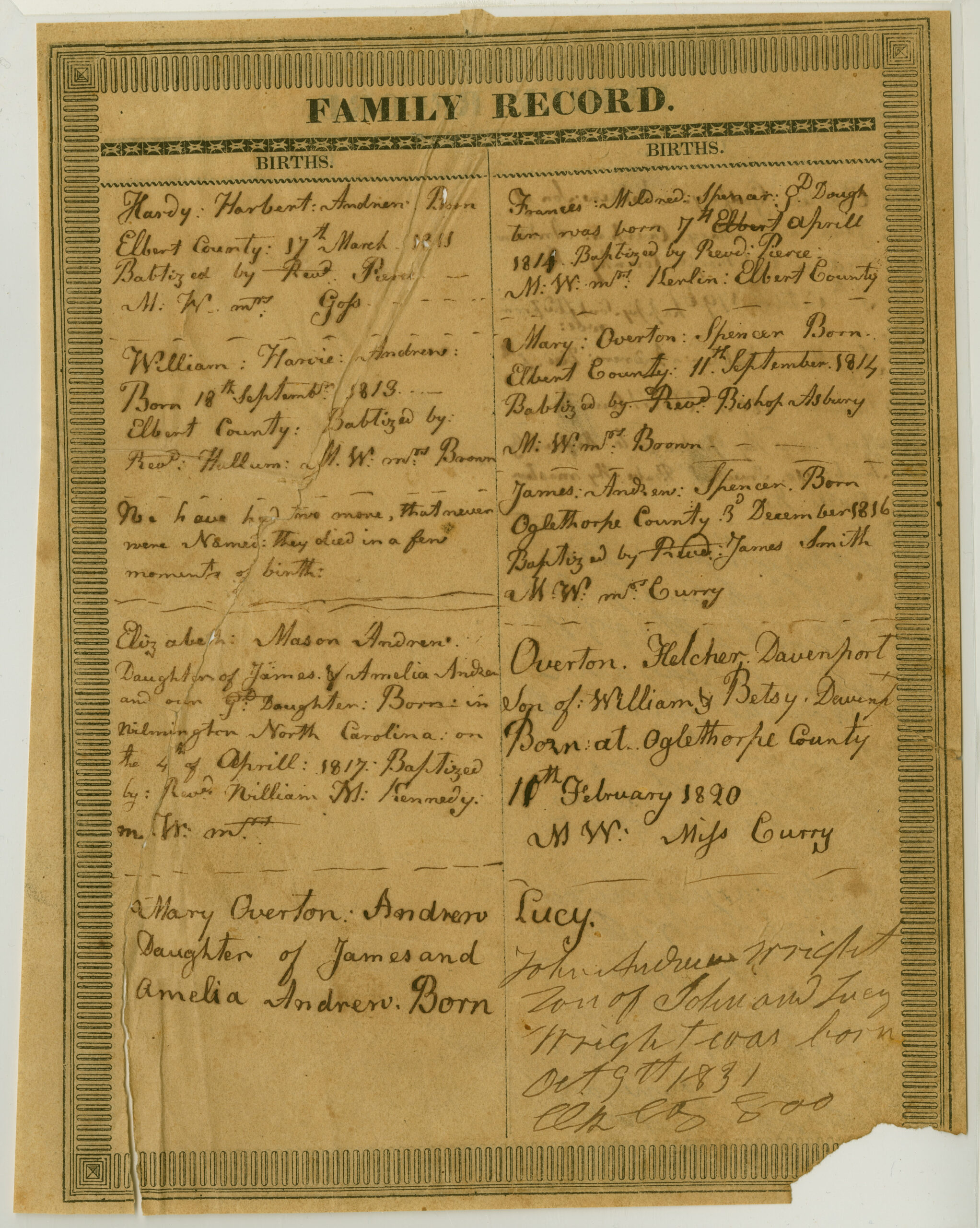

The marriages listed in the Andrew Family Bible include Bishop Andrew’s marriage to Amelia. Though Catherine has been described as part of the Andrew family, neither her nickname “Kitty,” nor her married name, Shell, nor the births of any of her children, are recorded in the Andrew Family Bible.

Andrew Family Bible

Detached pages documenting marriages and births from Andrew family Bible.

Andrew Family Bible, c. 1770s. Permanent loan of Salem Camp Ground, Oxford College Library Special Collections.

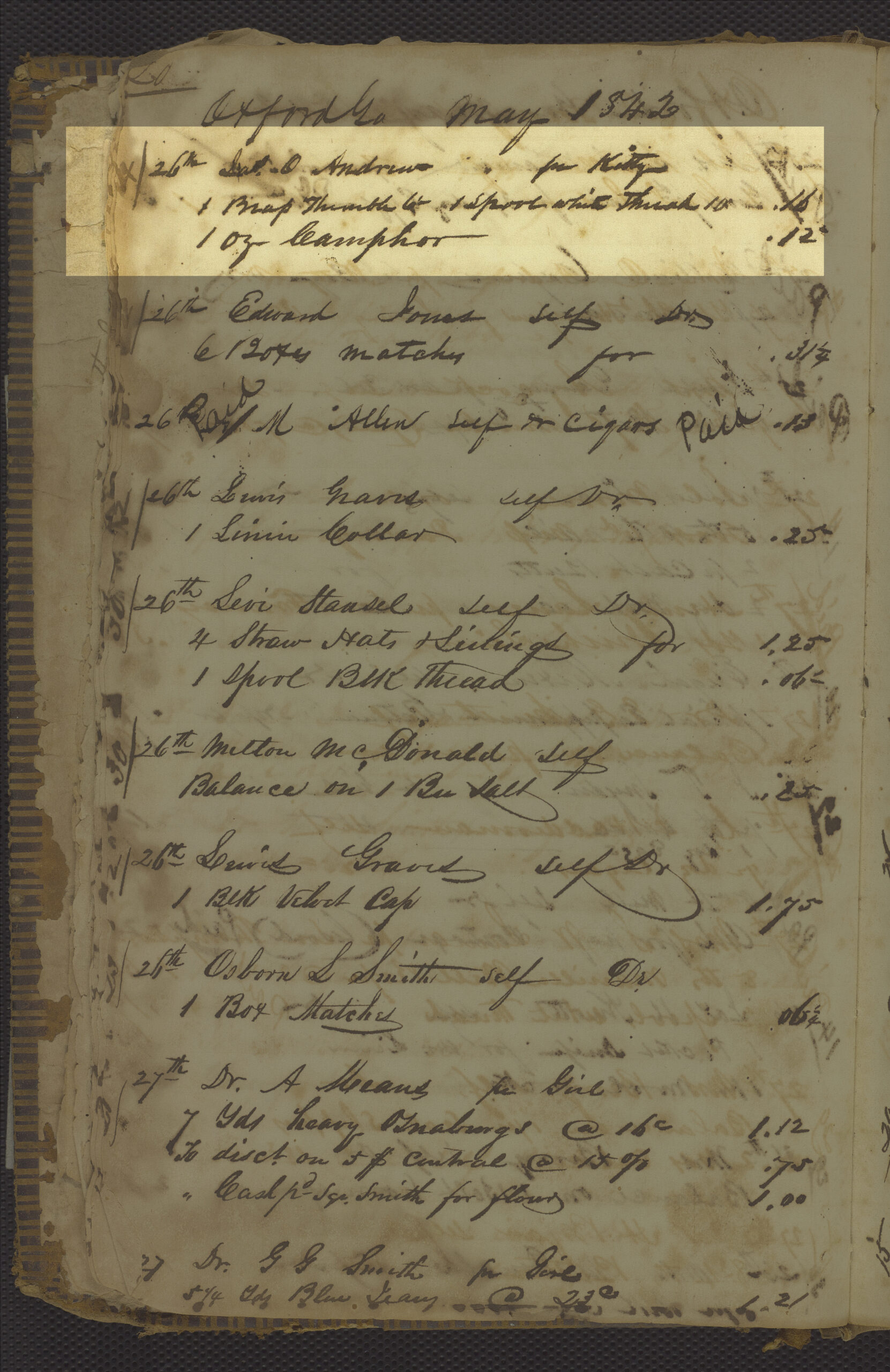

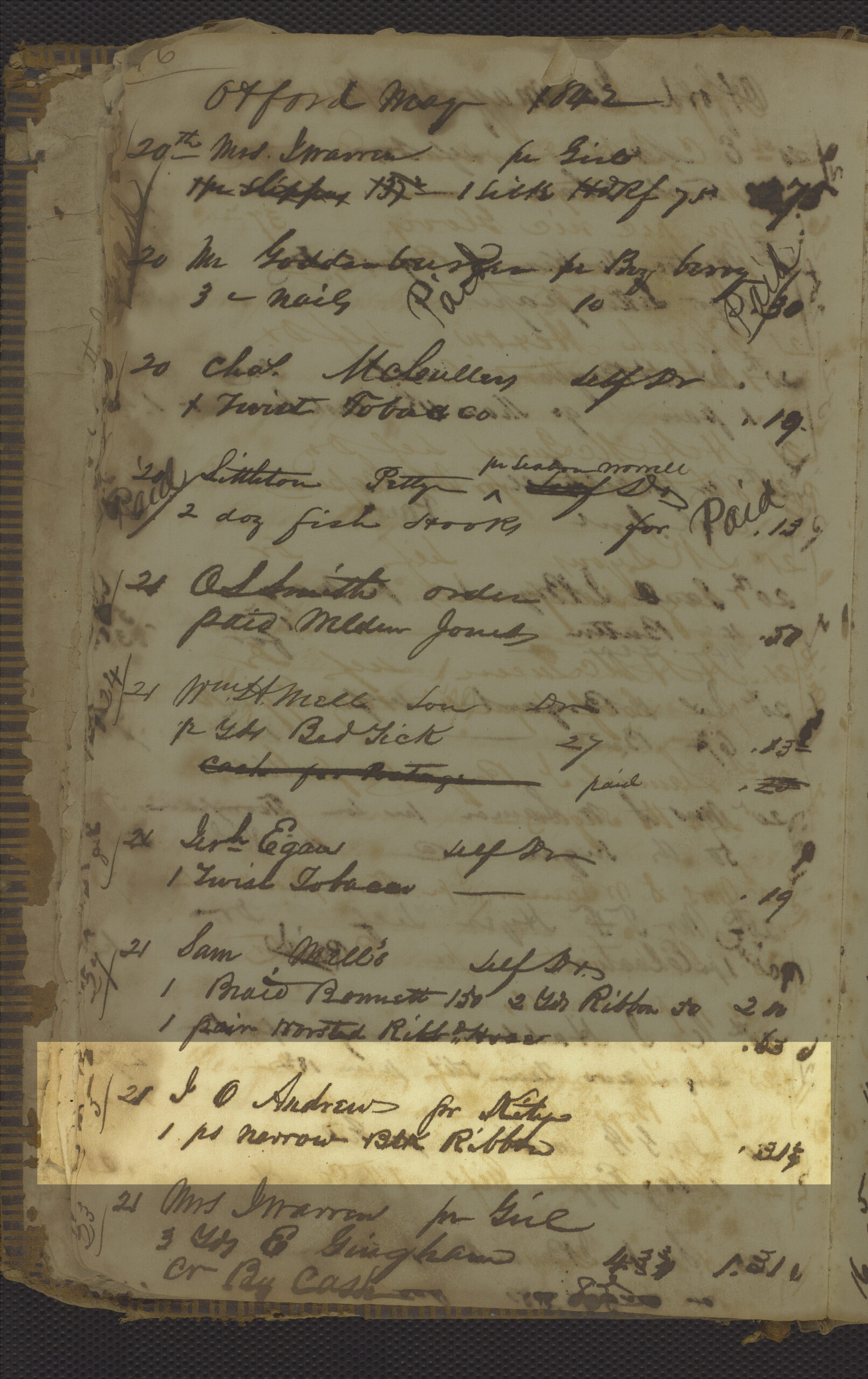

Multiple entries in this account book from the Graves General Store in Oxford document transactions made “for Kitty” on the Andrew family’s account. They include several purchases of sewing supplies, such as a transaction describing a silver thimble and pearl buttons, and other items. This record book serves as the only known direct evidence of Catherine’s life in Oxford.

Graves General Store account book, 1842

Excerpts of an account book kept by the Graves General Store in Oxford, GA. Four pages include notations of purchases made by “Kitty” on the Andrew family account.

Account Book, Oxford Store, 1842, Box: OBV5. Graves family papers, Manuscript Collection No. 327. Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/7/archival_objects/184383

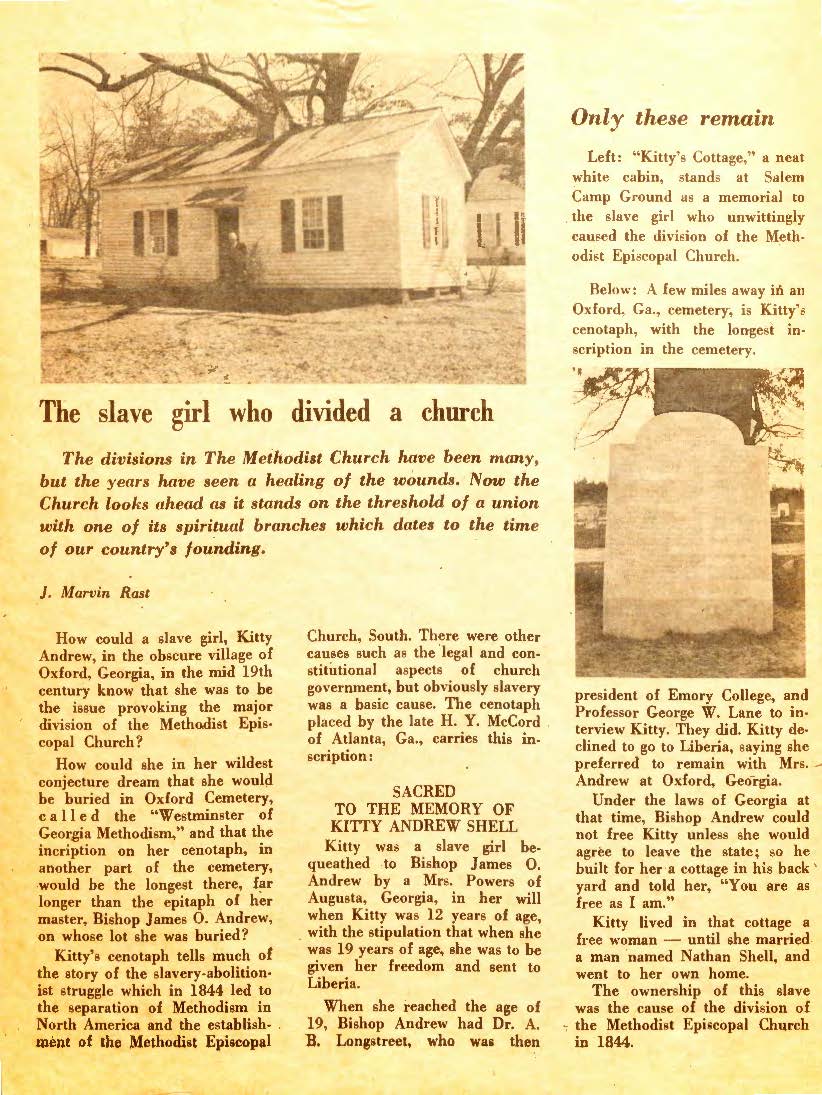

“Kitty’s Cottage”

The term “Kitty’s Cottage” has taken on multiple meanings since the building’s original construction. Relocated from its original site in Oxford to Salem Campground in 1938, it is now preserved near the site of Old Church in Oxford and maintained by the Oxford Historical Society. The cottage is a landmark still closely associated with the college.

Adding to white narratives of Catherine Boyd was the monument dedicated to “Kitty” placed in the Oxford Historical Cemetery in 1938 by a local businessman. The monument was notable in part due to its location in the cemetery, which was segregated. Catherine Boyd is the only person of color believed to be memorialized in the “white” side of the cemetery.1

Oxford Historical Cemetery, 1974

Visitors view the monument to “Kitty Andrew Shell” in the Andrew family plot at the Oxford Historical Cemetery.

Oxford Historical Cemetery, 1974, 4, Box: 10, Folder: 8. Oxford College Photograph collection, Series No. 025. Oxford College Archives. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/6/archival_objects/477710

Beyond physical markers, throughout the 20th century, depictions and stories of “Kitty’s Cottage” provided a sanitized narrative of Catherine Boyd’s enslavement by the Andrew family. The articles below, including one written by an Emory College alum, extend the pattern of white men describing a past for which there is little supporting documentation besides that created for the purpose of defending Bishop Andrew as an enslaver.

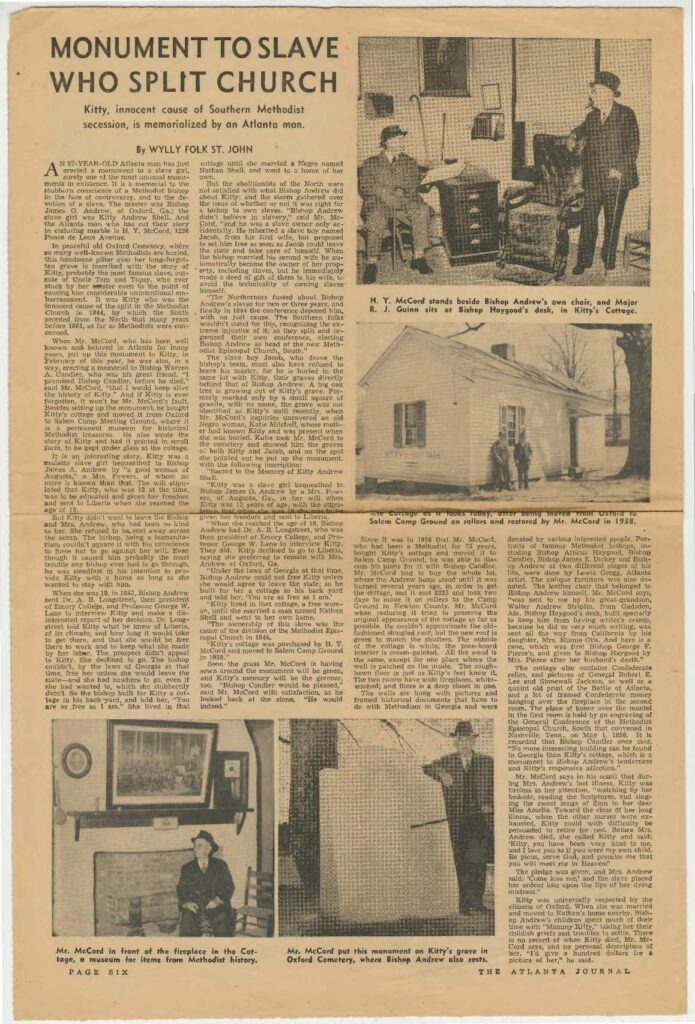

Atlanta Journal, 1942

St. John, Wylly Folk, “Monument to Slave Girl who Split Church,”May 3, 1942, Atlanta Journal. Found in: Houses – Kitty’s Cottage, 1939, 1942, undated, Box: 17, Folder: 17. Oxford Local History collection, Manuscript Collection No. 004. Oxford College Archives. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/6/archival_objects/474148

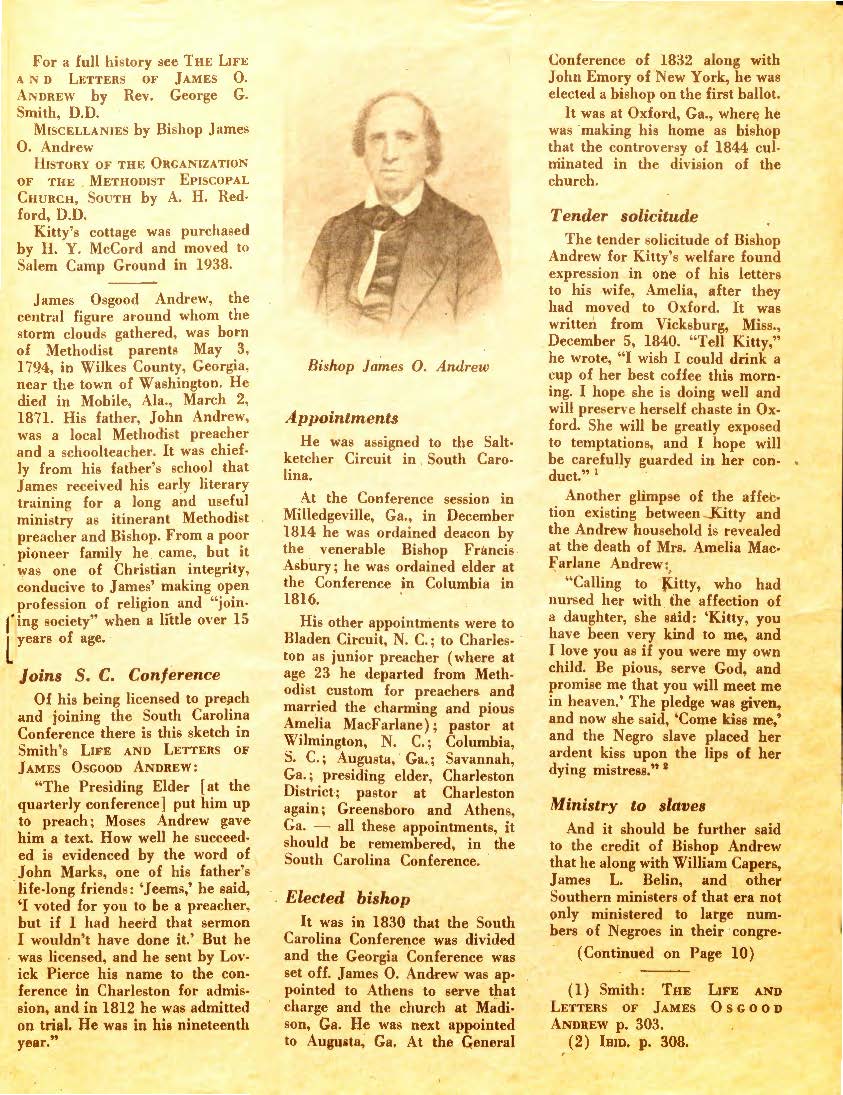

South Carolina Methodist Advocate, 1968

Rast, J. Marvin, “A Slave Girl who Divided a Church” April 11, 1968, South Carolina Methodist Advocate. Found in: Boyd, Catherinae “Kitty”, 1968, 1971, undated, Box: 1, Folder: 39. Oxford Local History collection, Manuscript Collection No. 004. Oxford College Archives. https://archives.libraries.emory.edu/repositories/6/archival_objects/473619

1. Mark Auslander, The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011), p. 139. See chapter The Other Side of Paradise”: Mythos and Memory in the Cemetery in The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family for a more in-depth exploration of history of the Oxford Historical Cemetary and Catherine Boyd’s Burial.